A very pestilent disease, my lord,

A very pestilent disease, my lord,

They call lycanthropia…

I’ll tell you.

In those that are possess’d with’t there o’erflows

Such melancholy humour, they imagine

Themselves to be transformed into wolves;

Steal forth to churchyards in the dead of night,

And dig dead bodies up: as two nights since

One met the Duke ’bout midnight in a lane

Behind St. Mark’s Church, with the leg of a man

Upon his shoulder, and he howl’d fearfully;

Said he was a wolf, only the difference

Was, a wolf’s skin was hairy on the outside,

His on the inside; bade them take their swords,

Rip up his flesh, and try: straight, I was sent for,

And having minister’d unto him, found his grace

Very well recover’d. – The Duchess of Malfi, Act V, Scene ii. (Webster, 1623/1997)

In honor of Halloween, we thought we would do a piece on werewolves. Wolves, intelligent, dangerous, creatures of the night, have only recently in history been eliminated as a threat to humans. The wolf is still a powerful image of intelligence turned inwards to serve the attainment of beastly desires. There are many legends of people who turn into wolf-like form for one reason or another. The ancient Greeks speak of Lycaon, King of Arcadia, who tried to fool Zeus into eating human flesh. But Zeus caught on to the trick and punished Lycaon by transforming him into a wolf (hence the root of our modern technical term for werewolf-ism – lycanthropy). The Roman Empire was founded by Romulus and Remus who were suckled and protected by a she-wolf. From Europe, to Africa, to Asia stories abound of those who turn into wolves at night, running amok trying to satisfy their lust for fresh meat. Lycanthropy as a medical condition similarly has a long history. Paulus Aegineta, a seveth century Greek described the syndrome. Likewise, Nebuchadnezzar was said to have suffered from something like lycanthropy in the aftermath of a long and severe depression. Supposedly St. Patrick turned Veneticus, King of Gallia into a wolf (Coll, O’Sullivan, & Brown, 1985).

In honor of Halloween, we thought we would do a piece on werewolves. Wolves, intelligent, dangerous, creatures of the night, have only recently in history been eliminated as a threat to humans. The wolf is still a powerful image of intelligence turned inwards to serve the attainment of beastly desires. There are many legends of people who turn into wolf-like form for one reason or another. The ancient Greeks speak of Lycaon, King of Arcadia, who tried to fool Zeus into eating human flesh. But Zeus caught on to the trick and punished Lycaon by transforming him into a wolf (hence the root of our modern technical term for werewolf-ism – lycanthropy). The Roman Empire was founded by Romulus and Remus who were suckled and protected by a she-wolf. From Europe, to Africa, to Asia stories abound of those who turn into wolves at night, running amok trying to satisfy their lust for fresh meat. Lycanthropy as a medical condition similarly has a long history. Paulus Aegineta, a seveth century Greek described the syndrome. Likewise, Nebuchadnezzar was said to have suffered from something like lycanthropy in the aftermath of a long and severe depression. Supposedly St. Patrick turned Veneticus, King of Gallia into a wolf (Coll, O’Sullivan, & Brown, 1985).

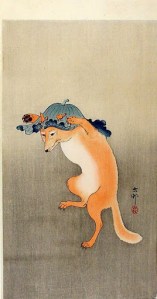

The Chinese and Japanese have legends of fox demons. In China these demons take the form of beautiful women in order to seduce unwary men, draining their life force through love-making. In Japan, the fox demons possess women by entering their bodies under their fingernails or through their breasts. Women possessed by a fox demon (kitsunetsuki) have changed features, looking more fox like. They are said to be ravenously hungry, especially for tofu, rice and sweet red beans. If cured the victims will never again be able to eat these foods. The phenomena of kitsunetsuki is considered by some psychiatrists and psychologists to be a culture-bound form of psychosis.

For some unknown reason, Wisconsin seems to be a focal point for werewolf sightings in the U.S. In 1936 a religious man named Mark Schackelman encountered a tall putrid smelling creature that had the features of both a wolf and ape while driving down a lonely highway. In 1964 Dennis Fewless had a similar encounter approximately two miles from where Shackelman saw his wolfman. And in 1972, a woman reported that a wolfman like creature had attempted to break into her home. In 1989 Lorianne Endrizzi saw a werewolf-like figure on the side of the road. Farmer Scott Bray also saw a similar looking creature around the same time period. As recently as 1999 in the same area, Doristine Gipson thought she had run over something in her car on a wet night. When she stopped her car to make sure she hadn’t hit anyone a werewolf-like creature jumped on to the back of her car. She sped off and the werewolf slipped off. After she told her story many local people came forward with their own tales of encountering the creature.

We may never know what was going on in Wisconsin, but we have a better idea about werewolves whose ‘hairiness’ is on the inside. There are a number of reports of lycanthropy in the psychiatric literature (Benezech, et. al., 1989; Dening & West, 1989; Fodor, 1945; Garlipp, et. al. 2004; Kulick, Pope, & Keck, 1990; Nejad & Toofani, 2005; Rosenstock & Vincent, 1977). In many of these cases the patients are suffering from psychotic delusions of being a wolf; behaving as they think a wolf would behave, thinking they have hair and claws, and acting out compulsive urges of bestiality, sexual licentiousness, and a desire to eat flesh. In some cases patients report being under the influence of the devil, their lycanthropy being intermixed with demonic possession. Some cases of supposed lycanthropy can be explained by purely medical causes such as hypertrichosis (where hairs grows all over the body), ingestion of ergot fungus (which contains the hallucinogenic lysergic acid), lepromatous leprosy, late stage syphilis, and severe congenital erythropoietic porphyria (Benezech & Chapenoire, 2005). However, when mental illness is prominent Rosenstock & Vincent (1977) report five typical characteristics in lycanthropic patients;

1. Delusions of being a wolf or other predatory animal. These delusions are often triggered when the patient is under extreme stress. These delusions may be psychotic and accompanied by hallucinations.

2. Preoccupation with religious issues including the devil and demonic possession. These pre-occupations vary according to the culture of the patient.

3. An almost obsessive need to be out at night, to frequent graveyards, and wild places.

4. Bestial-like aggressive and sexual urges.

5. Physiological signs of anxiety

The authors conclude that lycanthropy falls into six diagnostic possibilities; schizophrenia, psychosis with organic origins, psychotic depressive reaction, hysterical neurosis with dissociation, manic-depressive psychosis, and psychomotor epilepsy.

These psychiatric definitions are fine when the mental pathology is overt. However, there are a number of people who do not present any clearly defined pathology and yet consider themselves to be werewolves, other animals (therianthropes), or other creatures. The Otherkin are a subculture made up of people who consider themselves to be non-human. Their real or ‘true’ form may be an animal such as a wolf, or a mythological creature such as an elf, dragon, or vampire. Some Otherkin even believe themselves to be space aliens! Otherkin have a number of explanations for their ‘transpecied’ condition. Some believe in reincarnation, arguing that they retain vestiges of their animal habits from a previous incarnation, or that they are an animal mistakenly born as a human. Some Otherkin claim a totemic relationship to an animal. Much like some native peoples who believe that they are related by blood to creatures who share their world, these Otherkin form a strong spiritual bond to certain animals. Those who believe they are Otherkin may feel their bodies and instincts to be distinctly non-human. This could be a form of a hallucination or delusion, but these phenomena are specific to the feeling of being non-human and do not spill over into other aspects of the Otherkin’s life. Other explanations of the Otherkin include being transpecied (in the way that some people are transgendered), having non-human genes, being possessed by a non-human spirit, or having multiple personalities where one or more of the alters is non-human. The interesting thing about the Otherkin is they did not exist as a group until the internet facilitated communication among people with Otherkin beliefs!

Are the Otherkin and werewolves really so different than the rest of us? As Sigmund Freud wrote in his book Civilization and Its Discontents,

“Men are not gentle, friendly creatures wishing for love, who simply defend themselves if they are attacked, but that a powerful measure of desire for aggression has to be reckoned as part of their instinctual endowment. The result is that their neighbour is to them not only a possible helper or sexual object, but also a temptation to them to gratify their aggressiveness on him, to exploit his capacity for work without recompense, to use him sexually without his consent, to seize his possessions, to humiliate him, to cause him pain, to torture and to kill him. Homo homini lupus; who has the courage to dispute it in the face of all the evidence in his own life and in history? This aggressive cruelty usually lies in wait for some provocation, or else it steps into the service of some other purpose, the aim of which might as well have been achieved by milder measures. In circumstances that favour it, when those forces in the mind which ordinarily inhibit it cease to operate, it also manifests itself spontaneously and reveals men as savage beasts to whom the thought of sparing their own kind is alien. Anyone who calls to mind the atrocities of the early migrations, of the invasion by the Huns or by the so-called Mongols under Jenghiz Khan and Tamurlane, of the sack of Jerusalem by the pious Crusaders, even indeed the horrors of the last world-war, will have to bow his head humbly before the truth of this view of man.” (p. 103-104)

“Men are not gentle, friendly creatures wishing for love, who simply defend themselves if they are attacked, but that a powerful measure of desire for aggression has to be reckoned as part of their instinctual endowment. The result is that their neighbour is to them not only a possible helper or sexual object, but also a temptation to them to gratify their aggressiveness on him, to exploit his capacity for work without recompense, to use him sexually without his consent, to seize his possessions, to humiliate him, to cause him pain, to torture and to kill him. Homo homini lupus; who has the courage to dispute it in the face of all the evidence in his own life and in history? This aggressive cruelty usually lies in wait for some provocation, or else it steps into the service of some other purpose, the aim of which might as well have been achieved by milder measures. In circumstances that favour it, when those forces in the mind which ordinarily inhibit it cease to operate, it also manifests itself spontaneously and reveals men as savage beasts to whom the thought of sparing their own kind is alien. Anyone who calls to mind the atrocities of the early migrations, of the invasion by the Huns or by the so-called Mongols under Jenghiz Khan and Tamurlane, of the sack of Jerusalem by the pious Crusaders, even indeed the horrors of the last world-war, will have to bow his head humbly before the truth of this view of man.” (p. 103-104)

Things haven’t changed much since Freud’s time. A quick glance through recent human history shows that a beast still lurks in all of us. And this is something that is perhaps truly frightening.

References:

Benezech, M., de Witte, J., Etcheparre, J.J. & Bourgeois, M. (1989). A lycantropic murderer. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146(7), pp. 942.

Benezech, M.; Chapenoire, S. (2005). Lycanthropy: Wolf-men and Werewolves. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111(1), pp. 79.

Coll, PG., O’Sullivan, G., & Browne, P.J. (1985). Lycanthropy lives on. British Journal of Psychiatry, 147, pp. 201-202.

Dening, TR., & West, A. (1989). Multiple serial lycanthropy: A case report. Psychopathology, 22, pp. 344-347.

Fodor, N. (1945). Lycanthropy as a psychic mechanism. The Journal of American Folklore, 58(230), pp. 310-316.

Freud, S. (1930/2005). Civilization and Its Discontents. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Garlipp, P., Godecke-Koch, T., Dietrich, DE., & Haltenhof, H. (2004). Lycanthropy – psychopathological and psychodynamical aspects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109, pp. 19–22.

Kulick, AR., Pope, HG., & Keck, P. (1990). Lycanthropy and self-identification. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 178(2), pp. 134-137.

Nejad, A. G., & Toofani, K. (2005). Co-existence of lycanthropy and Cotard’s syndrome in a single case. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111, pp. 250–252.

Rosenstock, H., & Vincent, K.R. (1977). A case of lycanthropy. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 134(10), p. 1147-1149.

Webster, J. (1623/1997). The Duchess of Malfi (Drama Classics Series), London, UK: Nick Hern Books.

———————————————–